Before I write too many of these posts, I thought it best to take a pause and talk a little bit about something that is going to come up a lot: the distinction between systematic nomenclature and common names, and the differing roles that they each play.

A Shifting Attitude Towards Systematic Names

As I’ve progressed through my education in chemistry, my perspective on the importance of systematic names has altered. When the structure of organic molecules were first introduced to me back at the start of A-Levels we were taught to name them according to the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) conventions. This involved very specific rules with which we learnt how to construct a molecule’s unique name, and from this we should be able to redraw our molecule of interest. I had the impression that scientists nowadays used these names all the time and that any other names were assigned to history books and pseudoscience. The first lectures at university were a bit of a shock. Suddenly ethanoic acid became acetic acid, propanone became acetone, and little was really said about it. I came to accept that this just was how we talked now. My new working assumption was that systematic names were the gold standard; it would be great if we all used them, but the old names were a habit that was passed down from generation to generation.

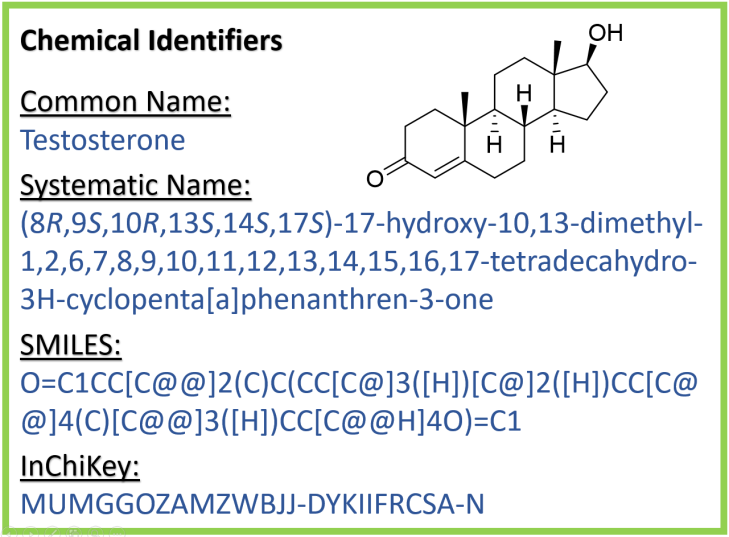

My viewpoint evolved further as I was introduced to more complicated molecules and went on to start doing research myself. I realised that it wasn’t possible to have a practical conversation about anything but the simplest of molecules if we had to use the long, convoluted names, with numbers inserted in seemingly random places. The vast majority end up being practically unpronounceable and would render casual comments about your work somewhat lacking in poeticism. For the science to be communicated efficiently, having shorter, pronounceable, memorable names is the only real option (see the example below). Until I started researching for this blog I assumed that this wasn’t the intention of those who first developed the naming conventions. I imagined that they had wanted there to be only one, unified language of organic chemistry with all other names abandoned, but that they hadn’t envisioned how complicated molecules could get. I was wrong.

The Beginnings of Standardised Systematic Nomenclature – The Geneva Congress

During the latter half of the 19th century, as more and more organic compounds became known to science, it became increasingly obvious that something had to be done about the mess of names that had sprung up. A few people had begun to make suggestions as to what a systematic nomenclature would look like, but opinions were many and agreements were sparse. It was in 1889 at an international congress in Paris that it was decided steps needed to be taken. A special commission was appointed, and for the next few years they met and discussed options and ideas and produced a report that laid out a provisional framework for the consideration of the chemical community.

Easter Monday 1892 saw the beginning of the Geneva Congress. Representative chemists from multiple countries were presented with the commission’s report, and they had one week to make some very important decisions. But their first point of business was to figure out exactly what they were trying to do. The French subcommittee were of the opinion that compounds should be allowed many different names, depending on which aspect you were trying to emphasise, particularly while teaching, and that the rules should be about how to arrive at these various names. The contingent from Germany disagreed, and argued that multiple names would be confusing to the research community, and that the aim of the week should be to agree on one official name for each compound. After much debate, the opinion of the Germans came out on top, and the first resolution of the Congress was passed by majority vote:

In addition to the usual name, every organic compound should be given an official name under which it may be found in indexes and dictionaries.

The Congress would like authors to adopt the custom of mentioning the official name in brackets in their publications after the name chosen by themselves.

So right from the beginning these official names were never designed to be used in normal conversations, or indeed as the sole identifier in written publications. Because of this, considerations based on how easy to say, or how pleasant to the ear these words would be were entirely unnecessary, as they were never expected to be said out loud. Chemists were expected to know how the names were constructed, and in the absence of a diagram be able to interpret them, but for the majority of the time the chemicals would be referred to by a simpler, vocalisable term. The result was words that were more like written formulae, and this principle is exactly how we use them today.

By the end of the week the congress had not managed to produce all the answers they set out to. It was only on the last session, on Friday morning that the important topic of aromatic chemistry even began to be discussed. However, a number of key decisions had been made, and the Geneva Rules were issued. These laid the foundation for further discussion. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry was founded in 1919 and in 1922 it organised a committee to continue working on the issue of nomenclature. By 1930 at new set of rules was approved.

As our understanding of the science has evolved, these rules have had to evolve with it. In fact, it seems that at times the language struggled to keep up. I learnt a lot of this information from a book entitled “Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry” by Maurice P. Crosland, published in 1962. Even at that time he felt it fitting to conclude his final chapter with a concerned quote from a 1948 writer “that systematic nomenclature is reaching breaking point and that human ingenuity can scarcely cope with it”. Seventy years later, I think we’re probably doing alright thanks.

Systematic Names and the Future

Systematic naming was clearly very important for much of the 20th century, largely as a method of indexing and ensuring that two people were definitely talking about the same thing. However, research chemists in the 21st century very rarely need to use the skills of constructing and interpreting systematic names in their day to day lives. With computer programs like ChemDraw these labels are automatically generated in one place, and automatically interpreted in another, and not necessarily read in the intervening time. For large complex molecules we often use the official name as a coded identifier, copying it from one place to another and generating the image which shows us what the structure is in an understandable way. In many such cases a compound number is just as useful, and takes up much less space on the page. It’s the generic names than remain in our minds. As we become more and more reliant on computers in our work, will the role of systematic names dwindle further and give way to computer-generated identifiers such as the InChIKey, or will tradition triumph and retain these naming conventions as an important part of a chemical education?

References

- Crosland, M. P. (1962), Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry. London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.

- Evieux, E. A. (1954), The Geneva Congress on Organic Nomenclature, 1892. Journal of Chemical Education. 31, (6), 326–327.

- Noyes, W. A. (1951), The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Chemical & Engineering News, 29, (14), 1290–1291.

Thanks Joe – I’d be interested in a similar introduction to other naming conventions (smiles, InChiKey etc) and CAS numbers of you have the time / interest

LikeLike

Excellent idea, I’ll add it to my list. Thanks

LikeLike

Great review, thank you. If you want the whole nine yards, if you want to know the actual names of chemists on the French and German teams and the their strongly held views on every detail imaginable, the definitive work is Verkade’s “A History of the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry” 1985.

It is, as they say, “an important book.” It’s not for the timid though, as Verkade’s style might be summed up as “Never say in one sentence what could be said in several paragraphs full of disclaimers about what you’ve said already and what you’re not going to say any more about — until the next chapter where you can say it all again.” 500 pp.

LikeLike